THERE is a certain rhythm to the European response to Mediterranean refugee tragedies . News of a disaster emerges. Leaders issue profound words of regret, accompanied by solemn pledges that such calamities cannot be allowed to happen again. A meeting is hastily arranged. But soon word comes that one country or another is unhappy about a particular proposed remedy, be it refugee-sharing or commonly resourced search-and-rescue missions. European officials begin to downplay expectations of a radical change in policy. The leaders meet, and argue. Some ideas are squashed, others sent to die in Europe’s bureaucratic machinery. What is left is trumpeted, not inaccurately, as a hard-won victory.

That is as reasonable a way as any to describe the developments in Europe this week, following the deaths of hundreds of would-be migrants in the Mediterranean last weekend. After three days of hasty preparation, the EU’s 28 heads of government met in Brussels last night for an emergency summit on migration. They agreed to take action in four areas: increasing surveillance at sea, fighting traffickers, cutting migration at the source, and sharing the burden of refugees more equitably.

The headline achievement was a tripling of the budget of Operations Triton and Poseidon, naval border-surveillance programmes that operate around the Italian, Maltese and Greek shorelines. The increase, to be funded from the European Union’s emergency reserve, means the operations will now have roughly the same budgets as did Mare Nostrum, an ambitious Italian-led search-and-rescue scheme wound up in late 2013. Thanks to offers from individual EU members it will also have notably more ships, helicopters and other assets at its disposal. (One country even offered a few dogs.)

Operation Triton responds to rescue calls but does not patrol the seas searching for vessels in distress. The death rate in the Mediterranean has rocketed since it took the place of Mare Nostrum, under which Italian vessels routinely entered the waters of north African states. So in the run-up to the summit activists and others had called for the reinstatement of a Mare Nostrum-style scheme with an explicit search-and-rescue mandate, with resources drawn from the entire EU rather than Italy alone.

Officials say that is not on the cards. Rewriting the mandate would take months, according to Donald Tusk (pictured), the president of the European Council. Yet they insist that it does not matter: the beefed-up Triton will be as effective as Mare Nostrum was. Asked how that can be possible, officials refer to the “law of the sea”, according to which all vessels, including commercial ships, must help rescue troubled vessels in their vicinity. That response, unsurprisingly, leaves many dissatisfied.

The British government, which pledged the services of HMS Bulwark (the Royal Navy flagship) and several helicopters, was among the more generous donors. David Cameron, the prime minister, also backed a call by Matteo Renzi, his Italian counterpart, for more assertive action against the people-smugglers. The EU will now prepare plans for a military mission, perhaps involving helicopter gunships, to capture or destroy trafficking vessels before they are used. In the absence of a functioning government in Libya that can request help such a plan will require UN approval: the leaders of Britain and France, the two EU members on the UN Security Council, have promised to begin the necessary legwork (both the Americans and Russians are said to be sceptical). In the meantime officials will heed Mr Renzi’s calls to consider more immediate forms of action.

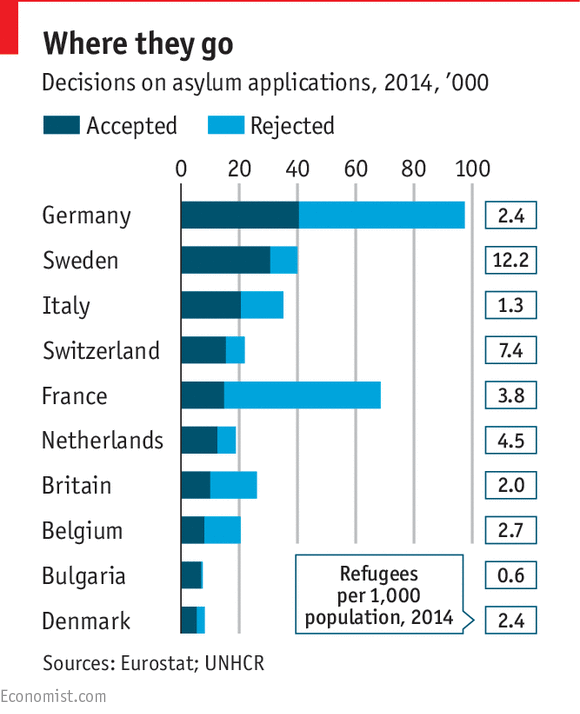

But Mr Cameron also insisted that Britain would not take in any additional refugees. This gets to the heart of the difficulties of forging a common EU migration policy. The leaders’ statement calls for a “first voluntary pilot project” on the resettlement of refugees across the EU. Britain and others insisted on the word “voluntary”. Germany, which accepts a disproportionate number of asylum-seekers, wanted it removed, implying an obligation on all members to take their fair share. The “logic” of these countervailing arguments, says an official, leaves you with a proposition that is vintage Brussels: “all countries must be engaged voluntarily”. The European Commission will hope to square this circle next week when it produces a roadmap for further work.

Sharing the burden of hosting refugees presents a conundrum that has foxed the EU for years. Generous countries like Sweden and Germany want others to take up the slack: two-thirds of migrants end up in just five EU countries, according to Angela Merkel, the German chancellor. The countries on the front line, like Italy and Malta, want the task of processing asylum-seekers to be redistributed. Everyone accepts that the Dublin regulation, according to which asylum-seekers should be dispatched to their European country of entry for processing, is a failure.

The problem is that no one knows how to devise a better system, because it would involve forcing some countries to take in more refugees than they want. The EU will have another go in the coming weeks, and leaders will discuss ideas at their next meeting in June. But, says a senior official, “I would not be overly optimistic”. There is little danger of that when it comes to the EU and migration.